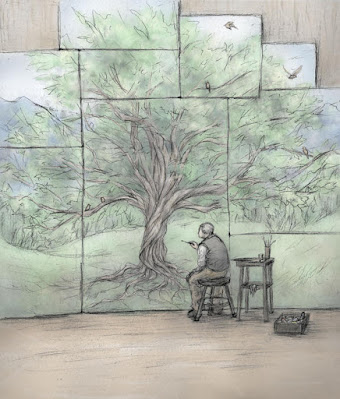

Niggle painting - by ejbeachy

One of Tolkien's most influential concepts was that of Subcreation; which he described in his essay On Fairy Stories as perhaps the most important justification for that genre we now term Fantasy (more exactly High Fantasy - which is characterized by 'world-building').

Subcreation is illustrated in the roughly contemporary short allegorical story Leaf by Niggle, which has usually been printed alongside On Fairy Stories as the volume entitled Tree and Leaf.

Leaf by Niggle is a really delightful, brilliantly-constructed work; which is also revealing of JRR Tolkien's own fears and hopes.

Towards the end of the story, the artist Niggle - having died and been through Purgatory, and with help from his previous neighbour Parish - is able to 'finish' his previously-only-planned Great Painting (allegorically equivalent to the totality of Tolkien's Legendarium); and also to have this painting become really-real (a place called Niggle's Parish) and actually to dwell in its sub-world.

Finally, Niggle passes on from his real-Subcreation towards 'the mountains'; and we hear (from some voices that represent aspects of God) that Niggle's Parish is proving to be very useful for souls emerging from Purgatory as 'a holiday, and a refreshment... for many it is the best introduction to the Mountains'.

Leaf by Niggle neatly encapsulates both the strength and limitations of Tolkien's concept of Subcreation - because on the one hand Subcreation is his justification for serious artistic activity and in particular imaginative and fantasy works...

But on the other hand, in the final analysis; even the most perfect and fully-realized Subcreative work - such as Niggle's Parish - is for Tolkien merely a recreation (holiday/ refreshment/ introduction). For Tolkien it is the Mountains that provide the highest spiritual destination.

My understanding of this is that the Mountains represent contemplation and worship. In other words, in Tolkien's scheme; Man's Subcreation - even at its most ideal - is a lower, temporary and transitional phase of spiritual growth; sooner or later to be set-aside in favour of inactive, immersion in God's creation.

I think that this represents Tolkien's (Roman Catholic, and indeed broadly traditional-Christian) theological view that Man cannot really add-to God's creation. God's creation is complete; and therefore the most any Man's Subcreative activity can do is 'rearrange' aspects of divine creation for particular purposes that have possible value at lower levels of spiritual development.

This seems to be an inevitable consequence of any monotheism in which God is attributed omnipotence and creation ex nihilo ('from nothing').

In a reality in which God already-knows and has-created every-thing, including every-thing about every Man; then there can be no truly original creation. Man's creativity can only be a sub-set of God's, because absolutely everything about Man is of-God.

Therefore, Tolkien's concept of Subcreation gives with one hand, but takes-away with the other; simply because every possible thing a Man might do from-himself is actually just a kind of 'game' played with bits of God's creation.

All possible creative activity by a Man can therefore only be partial and - at best - transitional; a kind of play, a pastime; to pass-time fruitfully en route to the Mountain peaks where all such activity is superseded; and Man becomes a purely-contemplative Being wholly-aligned with God's already-existing creation.

By contrast; my own theological understanding of Christianity is one in which Men live in God's creation, but God's creation is not complete and always developing and expanding; Man is truly free and is a god (of the same Kind as God but much less developed, and only fully divine in Heaven after resurrection).

Indeed, I see this development of Men to become co-creators with God as the primary reason for the original act of divine creation.

For me, therefore, Men are therefore able to add-to God's evolving creation, from their own divine and generative nature - and in a permanent way.

Subcreativity such as Niggle's - and Tolkien's - I therefore regard not as a pastime; but as an ultimately-valid activity; than which nothing is higher - and indeed this divine creativity of Man potentially includes divine procreativity: the begetting of Children of God.

There is only one primary creator, and we live in that reality; but creation is never finished; and it is Man's highest possible aspiration to participate in that creating.

It is the eternal commitment of resurrected Man to live by-Love which aligns all individual creative activity into harmony with the original divine conception.

The extent and nature of each Man's contribution to creation is part of his unique nature. So, although we cannot all be Tolkiens (or even Niggles!) in terms of Subcreative ability; it is the uniqueness of each Man's nature that makes every resurrected individual's creative contribution significant.